The cataclysmic explosion of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘apai volcano in January 2022 is reported to have been the biggest eruption recorded anywhere on the planet in 30 years. It sent a plume of ash soaring into the sky, left the island nation of Tonga smothered in ash, sonic booms were heard as far away as Alaska, and tsunami waves raced across the Pacific Ocean.

While the Tonga eruption was powerful but short, last year’s eruption of the Cumbre Vieja volcano on the Spanish Canary Island of La Palma was less explosive but lasted for almost three months.

Although different, both of these recent eruptions remind us all of how devastating nature can be. A better understanding of the natural processes that are occurring deep below our feet might bring the possibility of predicting eruptions a little closer.

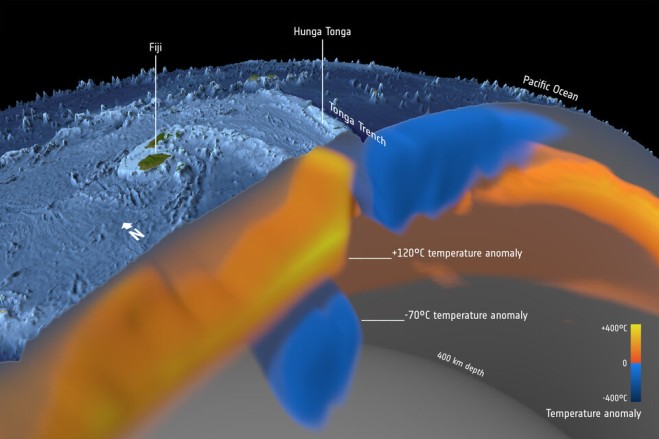

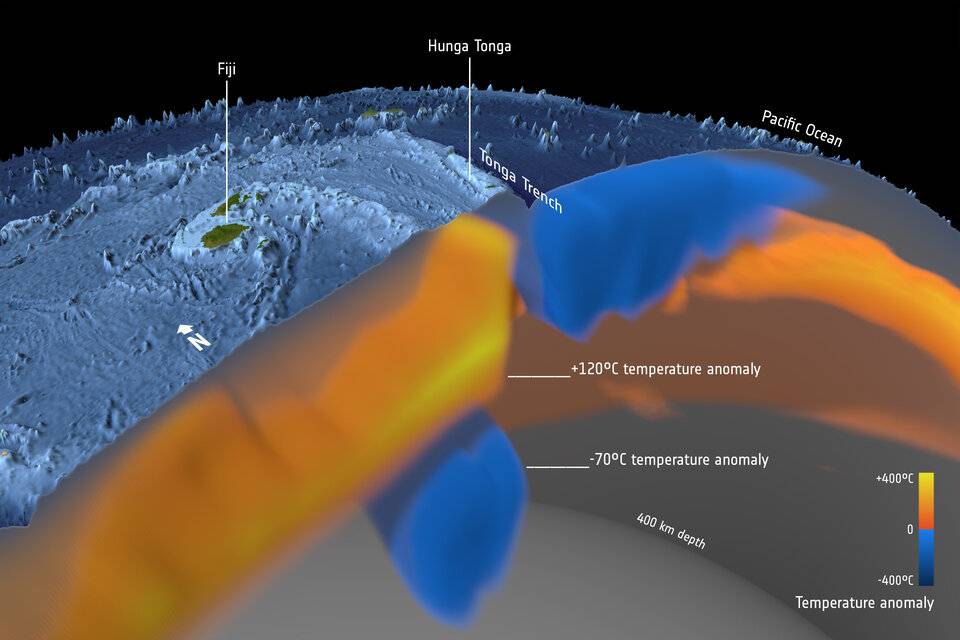

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘apai volcano is located in a back arc basin, created by the subduction of the Tonga slab. Back arc volcanoes are associated with the cold slab being melted by the mantle as the slab slides down into the mantle. It is a part of the Tonga–Kermadec arc, where the edge of the Pacific tectonic plate dives beneath the Australian Plate. In this image, seismic tomography shows the layer of hydrated, partially molten rock above the plunging Pacific Plate, which feeds the volcanoes of the arc. (Credit: ESA/Planetary Visions)