Like a sea captain tracking a white whale, Steve Miller has been chasing “milky seas” for decades. He has been looking for examples of a rare form of marine bioluminescence, and the arrival of new night-light sensing satellite instruments has allowed him to detect several of these rare events. It also has given scientists a better chance to sample future events.

Milky seas are a rare form of bioluminescence that mariners have described as looking like a snow field spread across the ocean. The steady white glow can stretch for vast distances, and it is not disturbed by ship wakes. Sailors have sporadically encountered this phenomenon since at least the 1600s, and Jules Verne dropped a reference to it into Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

Though there has been just one direct sampling of the phenomenon, scientists believe it occurs when populations of luminous (light-making) bacteria such as Vibrio harveyi explode in connection with colonies of certain algae and phytoplankton. Unlike typical bioluminescence—where phytoplankton emit light when they are stimulated, flashing briefly like fireflies—the bacteria in milky seas can stay lit for days to weeks. However, very little is known about the conditions in which they thrive.

In the early 2000s, while working for the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, Miller and colleagues began discussing the unique light signals that they might be able to detect with the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) that was being developed for the next generation of NOAA and NASA satellites. In particular, they were thinking about whether VIIRS would be able to detect any previously undetectable phenomena from space, such as bioluminescence in the ocean.

In new research published in July 2021, Miller and eight colleagues demonstrated that VIIRS could indeed detect the ghostly luminescence. Reviewing VIIRS data from 2012-2021, they found 12 instances of milky seas across the Indian Ocean and far Western Pacific. The signals from each event were invisible during the day—and so not attributable to some other reflective substance in the ocean—and persistent across several consecutive nights, drifting with the surface currents.

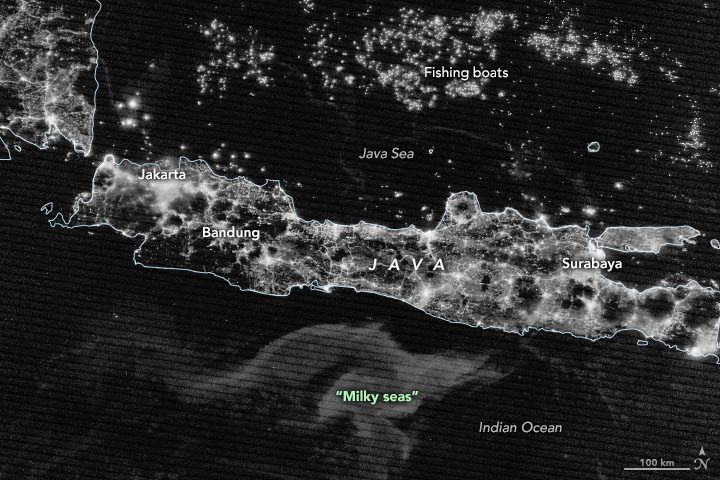

The VIIRS instrument on the NOAA-NASA Suomi NPP satellite acquired the accompanying image of Java and surrounding seas on Aug. 4, 2019. At its largest extent, the milky sea event spanned 100,000 square kilometers, about the size of Iceland. It began at the end of July and was still visible in early September, spanning two lunar cycles.

Image Credit: NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using VIIRS day-night band data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership, MODIS data from NASA’s Ocean Color Web, and data courtesy of Miller, S.D., et al. (2021).