The deadly volcanic eruption of Anak Krakatoa in 2018 unleashed a wave at least 100 meters high that could have caused widespread devastation had it been travelling in another direction, new research shows.

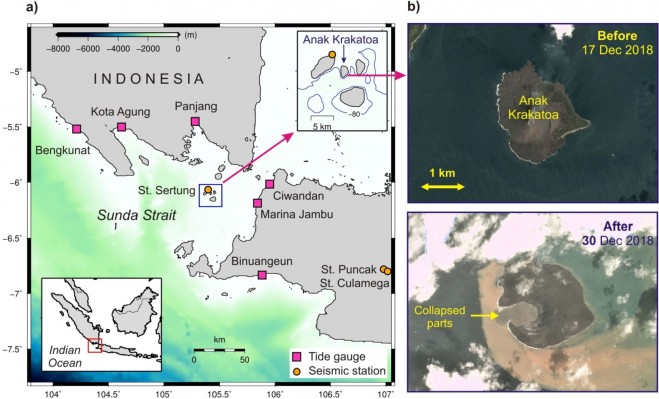

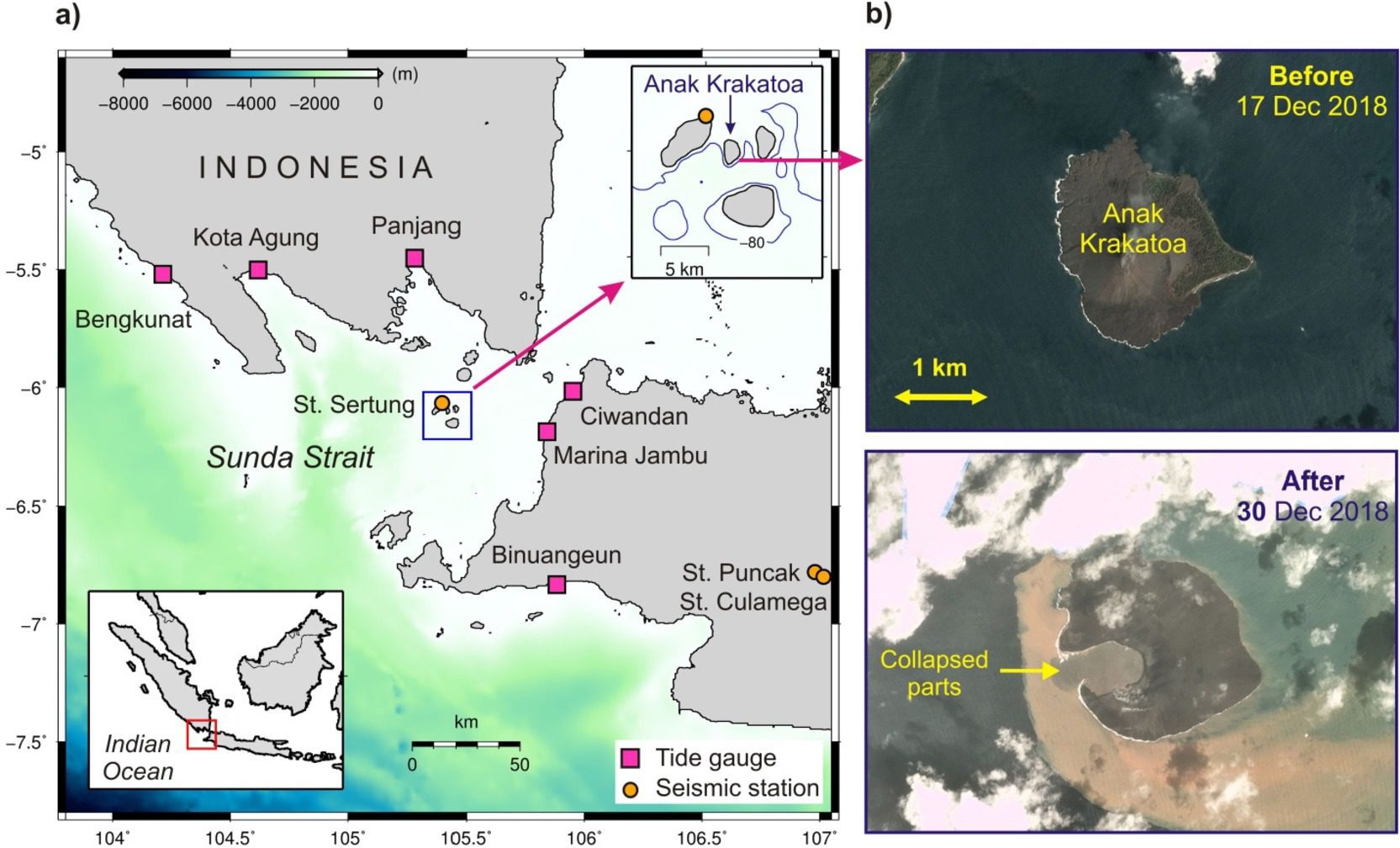

Over 400 people lost their lives in December 2018 when Anak Krakatoa erupted and partially collapsed into the sea, sending a wave westward toward the Indonesian island of Sumatra that was between 5 and 13 meters high when it made landfall less than an hour later.

However, new analysis from researchers at Brunel University London and the University of Tokyo has shown that the disaster wreaked could have been significantly worse had the wave—which started between 100 and 150 meters high—been travelling toward closer shores.

“When volcanic materials fall into the sea, they cause displacement of the water surface,” said Dr. Mohammad Heidarzadeh, an assistant professor of civil engineering at Brunel, who led the study. “Similar to throwing a stone into a bathtub, it causes waves and displaces the water. In the case of Anak Krakatoa, the height of the water displacement caused by the volcano materials was over 100 meters.”

Although the height of the wave quickly shrunk, thanks mainly to the joint effects of gravity pulling the mass of water downward and the friction generated between the tsunami wave and the seafloor, it was still more than 80 meters high when it hit an uninhabited island just a few kilometres away.

“Fortunately, nobody was living on that island,” said Heidarzadeh. “However, if there was a coastal community close to the volcano—say, within 5 kilomters—the tsunami height would have been between 50 and 70 meters when it hit the coast.”

For context, Heidarzadeh gives the example of the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, which generated a tsunami that struck land at a maximum height of 42 meters, causing at least 36,000 deaths at a time when the coastal areas were less populated.

The new research is important for coastal communities living near volcanos all over the world, said Heidarzadeh, as it’s the first to show that such a huge wave could be generated by the December 2018 Anak Krakatoa volcanic eruption.

The new analysis, published in the journal Ocean Engineering, used sea-level data from five locations near Anak Krakatoa to validate computer models which simulated the tsunami’s movement from the collapse of the volcano to landfall.