Researchers from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) recently discovered that infrared satellite data could be used to predict when lava flow-forming eruptions will end.

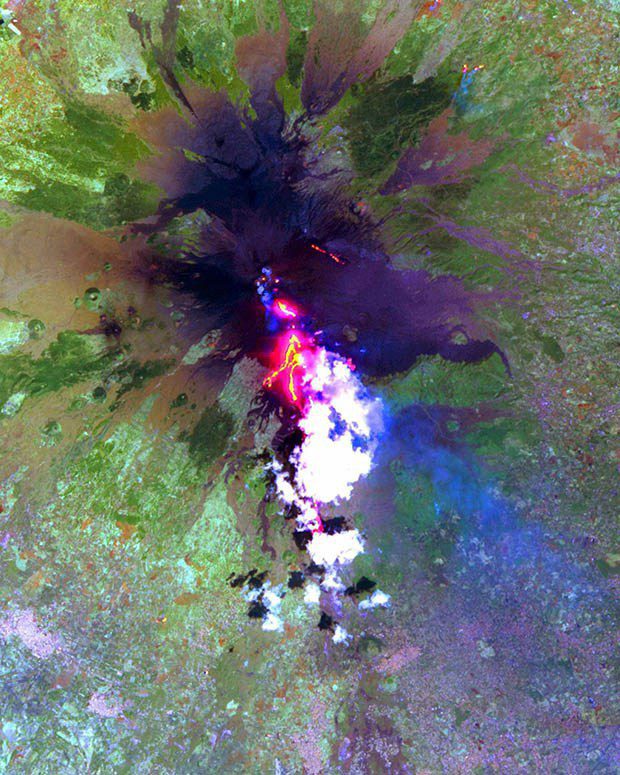

Using NASA satellite data, Estelle Bonny, a graduate student in the SOEST Department of Geology and Geophysics, and her mentor, Hawaiʻi Institute for Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) researcher Robert Wright, tested a hypothesis first published in 1981 that detailed how lava flow rate changes during a typical effusive volcanic eruption. The model predicted that once a lava flow-forming eruption begins, the rate at which lava exits the vent quickly rises to a peak and then reduces to zero over a much longer period of time—when the rate reaches zero, the eruption has ended.

Once peak flow was reached, the researchers determined where the volcano was along the predicted curve of decreasing flow and therefore predict when the eruption will end. While the model has been around for decades, this is the first time satellite data was used to test how useful this approach is for predicting the end of an effusive eruption. The test was successful.

“Being able to predict the end of a lava flow-forming eruption is really important, because it will greatly reduce the disturbance caused to those affected by the eruption, for example, those who live close to the volcano and have been evacuated,” said Bonny.

“This study is potentially relevant for the Hawaiʻi Island and its active volcanoes,” said Wright. “A future eruption of Mauna Loa may be expected to display the kind of pattern of lava discharge rate that would allow us to use this method to try to predict the end of eruption from space.”